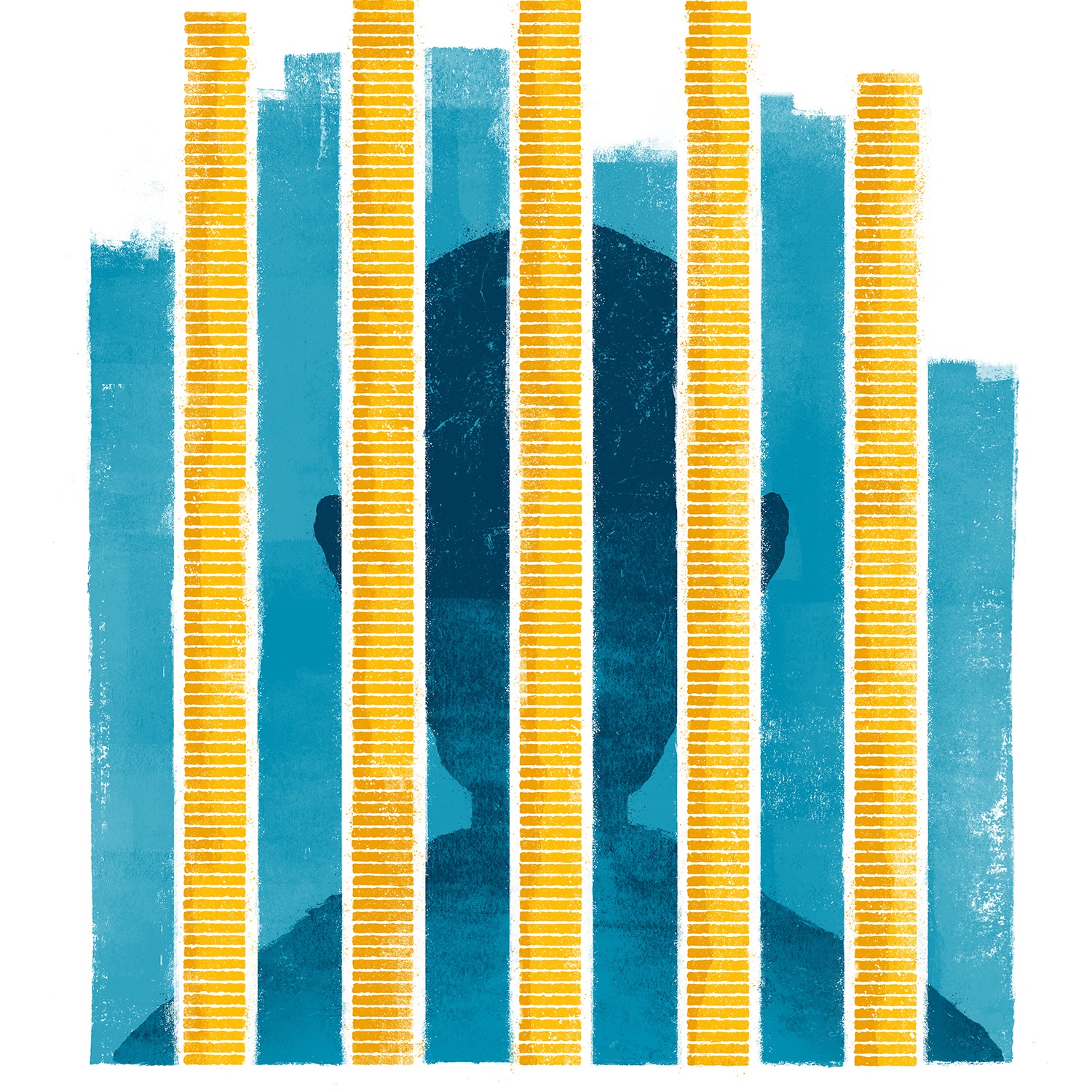

GILDED CAGE

The strange story of John Elwes, a man whose vast wealth funded the building of much of Marylebone, but whose extreme miserliness trapped him in a life of dressing in rags and eating roadkill

Words: Glyn Brown

Illustrations: Matthew Hancock

You think money’s going to make you happy, don’t you? Maybe it already has, for now at least. Everyone needs enough to get by, of course—but maybe what you need is just enough. Fiction and fact alike are stuffed with stories of wealthy misers who have let cash mess with their heads, because money can be a mistress with a liking for S&M. There’s a lot of money in this particular story, but little happiness; just anguish almost revelled in. And the worst of it is, the man in question had such potential for joy.

Our anti-hero is John Elwes, the tightwad on whom, it has been suggested, Charles Dickens may have based his portrait of Ebeneezer Scrooge. He was worth millions, but effectively lived on roadkill and wore what he could find or nick off tramps. He built much of today’s Marylebone, but crawled about homeless between the stunning Georgian houses he owned, dossing in the cold on any empty floor. But he was also kind to people, so the Scrooge comparison doesn’t really hold up. With friends in need, he was ridiculously generous, and too much of a gentleman to remind them that loans are usually repaid. It was himself he was hardest on. You look at his face as time passes. The marks of anxiety appear. Furrowed brow and worry. As he ages and resignation sets in, those lines become rigid. Soon he does look monstrous, furious. An example of how not to live.

Most of what we know about him comes from a long out-of-print book by Edward Topham, a flamboyant, elegant man, a journalist and playwright and friend of Elwes, though they couldn’t have been more different. You see a portrait of Topham—soigné, solid, pen in hand. Elwes, meanwhile, racked and cadaverous. Topham, who made a pile from this biography, wanted to show the best of Elwes, who could so easily have lived Topham’s happy life, and what exactly can go wrong.

A paranoid gene

Our boy is born John Meggot, on 7th April 1714 in St James’s, growing up in Southwark. His father Robert is a brewer but a wealthy one; John’s grandfather Sir George Meggot was MP for Southwark. Robert dies when John is four. John’s mother is Amy Elwes, granddaughter of Sir Gervase Elwes, a baronet and MP for Suffolk. Money all over the place. But Amy’s mother, Lady Isabella Hervey, was a well-known miser. I’ve hunted to see where this accusation comes from and it’s mentioned in the notes for the diary of her brother, John Hervey, 1st Earl of Bristol. The evidence if any, I suppose, comes in the fact that Isabella had four children; two died fairly young and the remaining two were Hervey Elwes, a miser of dastardly proportions, and Amy. It seems there’s a neurotic, even paranoid gene running rampant here because, her brewer husband dying, Amy reverts to what her mother perhaps told her was right, refusing to pay for food, and starves herself to death, leaving two small children, John and his sister (never named). Amy had just inherited £100,000 (roughly £8 million now) from Robert. John Meggot, now five or six, is left all that money, plus the family estate, which includes Marcham Park, a manor house in Berkshire.

John is sent to Westminster School. A good classical scholar, he loves books—but, already touched by self-denial, once he leaves school, he never reads again. But it’s early yet and he’s still relatively normal. He’s bad at maths and his friends (such as the young Lord Mansfield) borrow from him remorselessly. He doesn’t mind.

From Westminster, he moves to Geneva, where he concentrates on his horsemanship and becomes one of the best riders in Europe. He meets Voltaire, and many think he looks a bit like the poet and philosopher: pale and fine featured, good-natured and smiling. But Voltaire’s enlightened attitude doesn’t touch him. According to Edward Topham, “the horses in the riding school he remembered much longer”.

Living like an animal

Back in England, John at last meets his uncle, Sir Hervey Elwes, who lives, in his massive home in Suffolk, like an animal. John is going to be his heir, since Hervey has no children. Aged about 19 at this point, John “dressed like other people”. This is not acceptable to Hervery, so John learns to stop at an inn on the way and change into the ragged stockings and tattered waistcoat his uncle prefers. They sit in the freezing, echoing drawing room, watching a single stick of firewood burn, sharing a glass of wine—a sip for you, a sip for me. People are disgusting, Hervey insists, for wasting things. Aren’t they? The boy nods. You don’t want much to eat, do you? Jack shakes his head. Hervey was consumptive as a child; hidden away, he made no friends, became timid and shy, then became a hermit, scared of people; according to Topham, he was “vegetation in a human shape”. Funny but dreadful. Jack spends year after year with this man, visiting regularly. Hervey asks him to change his name to Elwes, and dies in 1763, leaving all he’s got, worth more than £250,000 (about £18 million now), to his nephew.

John Elwes walks into the big Suffolk house he now owns. The antique furniture is riddled with woodworm. Windows are cracked and papered over. Rain patters through the roof onto the floor. He’s 49 and is now seriously wealthly. Life has not been bad: John has lived in London, gambled with friends at his clubs. Topham describes his manners: “They were such, so gentle, so attentive, so gentlemanly and so engaging, that rudeness could not ruffle them, nor ingratitude break their observance.” Elwes has a “gallant disregard for his own person”. Even as an old man, apparently, he still “wished no one to assist him—he could walk, he could ride, he could dance, and he hoped he should not give trouble.” In fact, he’s out hunting with Topham in his 70s when a companion, useless at shooting, accidentally fires two pellets into his cheek. Blood everywhere. The companion is distraught, but Elwes, in pain but gritting his teeth, shrugs, “My dear sir, I give you joy on your improvement. I knew you would hit something by and by.”

So, what goes wrong? One, his friends have taken advantage, never paying back the money they owe him, so he starts to distrust people. Two, he’s spent too long sitting with Uncle Hervey. And three, he’s inherited treacherous genes. He begins to watch what he spends on himself, and that habit slowly takes control. Soon, he’s travelling everywhere on horseback, never in a carriage. Overnight journey? He puts two hard-boiled eggs in his coat pocket and any bits of bread he can find, and at night sleeps under a hedge.

No one quite realises what’s happening. But then his nephew, his sister’s son, comes to stay at Stoke. The nephew wakes in the night to find he’s getting rained on. He moves the bed again and again, finally finds an intact patch of ceiling and falls asleep exhausted. At breakfast, he tells his uncle. Says Elwes, “I don’t mind being wet myself, but for those who do, that’s a nice corner, isn’t it?” There’s an Addams Family feel to this. Elwes offers a hungry friend a piece of crushed pancake that’s been in his pocket for two months.

A beggar’s wig

By now, he has two sons by Elizabeth Moren, his Berkshire housekeeper. He loves John and George, but won’t let them be educated—that would put “ideas in their heads”. Often, he walks home in the rain, then sits in wet clothes because a fire to dry them costs money. He starts to eat putrid meat. He finds a wig in a bush, dropped by a beggar, and wears it. People laugh.

Meanwhile, he ponders London, where he can still sometimes be happy. He gets in touch with visionary architects the Adam brothers, and finances Robert Adam to begin building Portland Place, constructed speculatively in the hope of attracting buyers. They decide on a slimmed down version of the aristocratic style used in grand houses. Portman Square is erected, along with the riding-houses and stables for the Life Guards, at the time headquartered both in Knightsbridge and here. The project becomes huge. It’s likely Elwes is also the source of the money behind the building of Devonshire Street, Weymouth Street, Quebec Street, parts of Harley Street, and Baker Street. Without Elwes, it’s uncertain the Marylebone we know would exist.

And when he visits London now, he simply kips in whichever of his properties is currently empty. Really empty: each has a few chairs, sometimes a table. He’ll sit in a new mansion on Great Marlborough Street, make a fire with woodchips left by the carpenters, stick oiled paper in the windows, sleep on a pallet of straw. At dusk, he’ll go to bed—that saves a candle.

And then something happens to occupy his mind. At 60, Elwes is elected as an independent MP for Berkshire. It’s a halcyon 15 years, when somehow the weight of money is pushed back. He’s utterly upright, accepting no backhanders, refusing a peerage, taking no income. He still dresses like a tramp—people give him money in the street thinking he is one. But he attends meetings, sits in clubs discussing affairs of government, makes wise decisions. He absolutely reeks, but he smiles and seems happy.

Ashamed and embarrassed

The moment he’s retired from politics, though, he begins to starve himself and sit in the dark again. When parliamentary friends invite him to the Mount Coffeehouse in London, he blossoms pathetically—stretches his hands toward the fire, squints like an owl in the glowing candlelight. He has a cultured palate, loves French food and wines, but only if other people pay for them. Otherwise he just gazes, watching them eat. Sketches of him in parliament show a handsome man, but now his appearance goes downhill. In Suffolk, he snatches half a moorhen off a rat and chomps it; he eats a half-digested pike he finds by the river. His servants are ashamed and embarrassed. He’s more and more obsessed with his only love; he begins to get up in the night and count an amount of five guineas, which he wraps in paper and hides in his desk. He’s become Gollum—the emaciated body, the sad, wracked face.

When he becomes briefly ill, Topham gets him to write a will, leaving everything to his two illegitimate sons. A doctor is astonished; Elwes is strong because he walks everywhere, and with no excess weight he has no gout. If his mind wasn’t broken, he could live into his nineties. But it is. Within months, he’s lost the last of his marbles. He sleeps in his coat, shoes and old torn hat, with his walking stick. On 26th November 1789, at 75, he asks his son if he has “left him what he wished”. And then he dies.

I’m looking up the psychology of the miser. A person trapped in a cage of fear who can’t give money or deep love, and is terrified of loss of control. Superficial, but that could be a boy who loses a genial father at four, and a mad, broken mother at six.

I don’t care. Having got this far, I’ve lost patience with him. It’s not as if he’d once been poor and been thrifty out of necessity. I look at that parliament illustration of him again, that handsome face, and want to slap it. The point of money, once you have enough, is surely to try to do good with it. Elwes did construct exquisite buildings, though only for investment. But what I think we should all do now is take a walk down Welbeck Street, think of him, then go and buy ourselves or someone else something silly, just for the hell of it. Doesn’t have to be big. But it has to be done.